The Rise and Fall of the Labor and Union Movements in America

The Labor Day Holiday is celebrated annually on the first Monday of September. It is considered the unofficial end of summer (although summer actually lasts until the Autumn Equinox the 3rd week of September) and is marked by picnics, concerts, festivals, back-to-school sales (although many schools now start school in mid- or late August), and lastly Labor Day parades.

Here in Michigan, there is the annual walk across the Mackinaw Bridge (also known as the “Mighty Mac”) that separates the Lower Peninsula from the Upper Peninsula, usually led by the current governor of our state. The Mackinaw Bridge is the largest suspension bridge in the western hemisphere.

Michigan also has a big labor movement history, especially for the auto industry, so Labor Day is still marked by parades by union members in towns and cities all over the state.

In Detroit, the long Labor Day holiday weekend is also celebrated with the Detroit Jazz Festival, the largest free jazz festival in the world, which brings music lovers from all over the world to downtown Detroit. The festival, which spans four separate performance stages with scores of concerts over four days, celebrates its 40th anniversary in 2019.

The History of Labor Day

The entire actual purpose of Labor Day in the United States is to celebrate the achievements of American workers. It was first created by the labor movement in the late 19th century and became an official federal holiday in 1894. Labor Day is an acknowledgment of not only the contribution of American laborers but also the often factious and deadly growth and decline of the labor movement in America.

Before labor unions as we know them now existed, there were trade unions that started in the late 18th century and worked to improve working conditions and protect pricing for the skilled trades. Throughout most of the 19th century, industrial workers were not considered part of the labor movement.

In the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution started its rise and many people left the farms to move to the cities to work in factories, mines, and mills owned by wealthy businessmen and large corporations. The average worker in these environments often worked 12-hour days, seven days a week at very low wages just to make a basic living. The conditions for the workers, who were usually the very poor and recent immigrants, were unsafe, unsanitary, and exploited the workers, including children as young as five years old.

Many employers of that time saw their workers as dispensable human stock, not caring if their employees got sick, were hurt, or were killed on the job because they could be easily replaced with another body. Labor unions sprung up during these years to organize strikes to protest the horrific working conditions, and to petition the employers and corporations to offer better working hours and higher pay.

Many of those protests turned violent, including the notorious Haymarket Riot of 1886, and the Bayonne Refinery Strikes of 1915–1916. On September 5, 1882 (the first Monday of September), over 10,000 workers took unpaid time off to march to Union Square in New York City, thus holding the first Labor Day parade in the history of the United States.

Although Labor Day was celebrated in many of the cities and industrial centers in the country, it wasn’t until the employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company went on strike, and boycotted all Pullman railroad cars, causing a devastating crippling of the nationwide railway system, that President Grover Cleveland created the national Labor Day Holiday.

The Modern Labor Movement

Photo by Robuart on 123rf.com

In the early twentieth century, just as in the rest of this country, trade and craft unionism morphed into an organization that was racist and sexist, disallowing interracial local chapters and excluding women and eastern Europeans.

The “whites-only” policies for the higher-level trades and job opportunities even in the factories, where the best-paying jobs such as machinists were offered only to white men.

The growth of the labor movement in the 20th century still saw many protests, strikes, and deadly riots in the United States and many countries around the world, including the 1932 riot at the Dearborn, Michigan, Ford plant where police called in to squelch the outbreak killed several workers.

It was only after World War II that the labor movement gained significant power and political influence. Union members, through the solidified collective bargaining methodology, secured increased wages, job security, guaranteed pensions, and medical benefits.

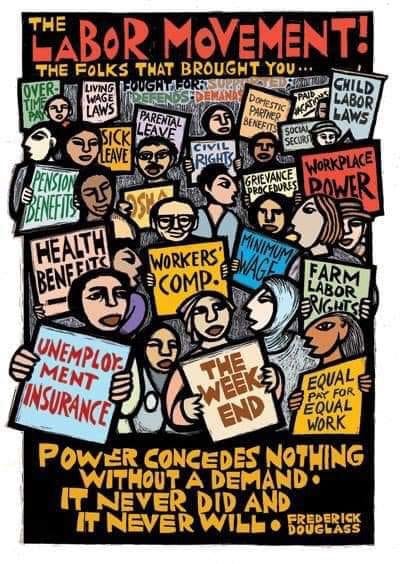

Eventually, however, the labor movement and the fight for workers’ right yielded many benefits to union and non-union workers alike, including:

the 8-hour workday

the two-day weekend

child labor laws

safety regulations

regular lunch hours and breaks

higher salaries

medical, dental, and pension benefits

paid holidays and vacations

However, the labor movement still only affected about one-third of American workers, and it wasn’t until the 1960s when the public and service sectors set up unions for their workers that minorities and women were allowed to move into leadership positions within the various unions.

The Decline of the Influence of Labor

The decline of the influence of labor actually started right after World War II with the 1947 passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, which severely restricted the rights of workers to strike, initiated the proliferation of “right to work” laws which provided union-only shops, and supposedly protected the United States against the perceived influx of communist and socialist ideologies into the unions.

By the 1970s, with the upswing in deregulation in the communications and transportation industries, and the huge influx of foreign goods, especially after the 1973 oil embargo, American goods lost a great deal of their competitive edge. By the time Ronald Reagan became president in 1980, anti-union sentiment grew to its highest level since before the Great Depression. The watershed moment of union-busting was the 1981 air traffic controllers strike by members of the Professional Air-Traffic Controllers Association (PATCO). PATCO failed in negotiations with the federal government to raise their wages and improve their working conditions, and 13,000 members went on strike on August 3, 1981.

Two days later, President Reagan declared the strike illegal, fired all of the controllers, and declared a lifetime ban of rehiring any of the strikers by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Later many other local, state, and federal organizations decided that strikes by public sector workers like teachers and police officers would be declared illegal.

Automation, the search for cheaper labor, and the influx of foreign corporations led to the further demise of the influence of labor unions. Between the end of World War II and the end of the 20th century, union membership fell from about 33% of the workforce to less than 14% of the workforce.

The Loss of Unions Also Meant the Loss of Middle-Class Status for Many

Economic conditions, including the devastating 1980–1982 recession, continued the decline of the strong middle class that the union movement had built in the mid-20th century. The penchant of Republican administrations for tax cuts for the wealthy that were supposed to spur “trickle-down” benefits to the middle and lower classes, further eroded the power of industrial and corporate workers to negotiate higher wages and better working conditions.

The 1980–1982 recession was the worst since the Great Depression and until the 2008–2010 Great Recession, which was then the worst. People lost their jobs, their homes, their economic security, and the income gap between the rich and the middle and the lower economic classes greatly increased.

Today’s Employees are Pretty Much on Their Own

Today, the majority of the workforce is younger, more diverse, more mobile, and often usually work at lower-paying jobs. Although guaranteed pensions are a thing of the past, most of the other benefits initiated by the union movement in the mid-20th century are now entrenched in the employment laws and policies of corporations. That often means that today’s workers see less of a need to join a union.

However, unlike the days when people could graduate from high school and work right into a high-paying job that provided a middle-class lifestyle for life, today it is almost impossible for young people to leave high school or even college and make enough to buy a car or a home.

Without the protection of strong unions, most employees are now on their own to negotiate their own salary and benefits packages, and companies are much more able to structure those packages to benefit the bottom line rather than the workers.

Although it seems longer, it was only about one generation or so of the American workers’ lives that truly benefitted from strong unions, from about the 1950s to the 1970s. Since then, little by little, the wealthy have become much wealthier, the middle class has greatly shrunk, and the lower classes often have to depend on welfare and other government programs to make ends meet even when they have jobs.

With the demise of the labor movement and strong union influence, how can America rebuild the middle class and ensure that everyone has access to a living wage, economic security, and adequate health care? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Keep up with everything going on with me and my businesses by joining our email list. Weekly updates and we promise, no spam!

About Me

After a 35+-year career in education (Pre-K — 14), collaborative sales, and sales management and marketing, I started my first writing and editing business, Writing It Right For You, in July of 2008; expanding to my second, Detroit Ink Publishing, in 2012, and my third, Your Business Your Brand Creatively, in 2014. In 2018, I merged Writing It Right For You into Your Business Your Brand Creatively.

Through my three companies, my clients learn that “It Matters How You Say It”! I work with solo professionals, creative freelancers, and small businesses throughout the United States, Canada, the U.K., and twelve other countries on a variety of writing, editing, publishing, branding, and marketing projects.

I am an author and public speaker, and I also host a weekly podcast: “The YB2C Live! Podcast for Entrepreneurs.” (https://yb2clive.libsyn.com/) .”