The Sordid History of Lynchings and State-Sponsored Murders in America

Death is final, for the victim and for the accused.

Issue #736 The Choice, Tuesday, October 1, 2024

Please share and subscribe to help us grow this publication.

If you like us, REALLY like us, please click the “Like” button at the end of this post!

We appreciate your support!

Introduction

Some people believe in the death penalty in most or all cases. Some people are against the death penalty in all cases.

No matter what you believe, it is true that throughout American history, lynchings and death penalty executions have negatively affected Black and brown people. Both are final: there is no “coming back” after you are dead.

There are several recent incidences of people on “death row” found to be innocent after new information or DNA tests were found and applied to their cases.

Lynching

Lynching, a term primarily associated with non-court authorized killings by mobs, became prevalent in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The practice took its name from Charles Lynch, a Virginia planter and justice of the peace who headed an irregular court to punish loyalists during the American Revolutionary War.

However, it was post-Civil War America that saw an explosion in lynchings, especially in the Southern states. After the end of slavery in 1865, white supremacists, threatened by the potential shift in social and economic power, resorted to terror and violence to maintain their dominance. Lynching became a brutal method for reasserting white supremacy and stifling black progress.

The Terror of Lynchings

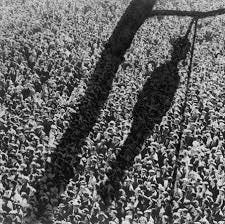

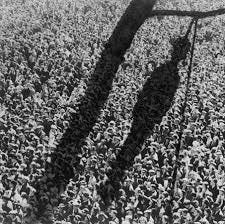

From 1882 to 1968, about 4,743 lynchings were documented in the United States, according to the Tuskegee Institute. The vast majority of these victims were African American men. These acts of violence were often public spectacles, attended by large crowds, and even advertised in local newspapers. Innocent victims were subjected to unimaginable brutality—beaten, burned, mutilated, and hanged—under the pretext of justice. More often than not, the accusations against them were false or grossly exaggerated.

Lynchings were intended not only to punish the individual but also to instill fear within the African American community. They served as grim reminders of the consequences of stepping out of line in a society built on racial segregation and discrimination.

There are still incidences of lynchings today, although they don’t get nearly enough attention.

State-Sponsored Murders

While mobs carried out lynchings, state-sponsored murders denote violence perpetrated or condoned by the authorities. These include the use and misuse of the death penalty.

The case of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American boy brutally murdered in Mississippi in 1955, is one of the most infamous examples. His killers, although known, were acquitted by an all-white jury, highlighting the collaboration and complicity of the justice system in such acts.

The Death Penalty and Racial Bias

The death penalty in the United States has also been criticized for its racial bias. Studies have shown that African Americans and other non-white Americans are disproportionately sentenced to death, particularly when the victim is white.

Cases like that of George Stinney, a 14-year-old black boy wrongfully executed in South Carolina in 1944, underscore the systemic injustices inherent in capital punishment.

There was also the case of the “Central Park Five,” five Black and brown teenagers who were falsely accused of raping a white woman in Central Park in 1989: the young men were convicted of the charged offenses and served sentences ranging from seven to thirteen years.

More than a decade after the attack, while incarcerated for attacking five other women in 1989, serial rapist Matias Reyes confessed to the assault and claimed he was the only actor; DNA evidence confirmed his involvement. The convictions were all eventually vacated.

Famously, Donald Trump, a known racist, took out a full-page ad in the New York Times calling for the immediate execution of the “Central Park Five." After the group was found to be not guilty, Trump refused to apologize for his call for their killing. The young men are now collectively known as “The Exonerated Five," and one member, Yusef Salem, was elected to the New York City Council.

So far in 2024, through September 30, 18 men have been executed in Texas (4), Alabama (4), Oklahoma (3), Missouri (3), Utah (1), Florida (1), Georgia (1), and South Carolina (1)—all “red” states. The majority of those executed were Black or brown.

Marcellus “Khalifa” Williams, a Black Muslim, was executed last week in Missouri, even though DNA evidence recently revealed that he was innocent. The governor and the state supreme court refused to halt his execution.

These executions represent just the most recent instances of state-sponsored use of the death penalty in the United States. Each case provides insight into the ongoing debate over capital punishment, particularly in light of concerns about racial bias, judicial fairness, and the moral implications of state-sanctioned death.

The Aftermath of Lynchings and Executions and the Continuing Struggles

The legacies of lynchings and state-sponsored murders are still evident today. The trauma of these brutal acts has been passed down through generations, contributing to the racial disparities and tensions that persist in American society. Efforts to address this history, such as establishing the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, are crucial steps in acknowledging and healing these wounds.

Conclusion

Lynchings and state-sponsored murders represent some of the most egregious violations of human rights in American history. They are stark reminders of our nation's struggle with racism and violence since its inception.

Confronting this past is not just about acknowledging the horrors inflicted upon primarily African Americans but also about committing to a future where justice, equality, and humanity prevail.