The Separation of Church and State

Christian Nationalism, which is the opposite of democracy, is again on the rise in America.

Issue #313 Government May 4, 2023

Christian Nationalism is the belief that America was founded on Christian principles and should be a Christian nation.

Lately, Christian Nationalism has become a raison d'etre for many MAGA Republicans, including Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, and Tim Scott of South Carolina. People like these have insisted that the Christian church should dictate what happens with the government and suggest that the Bible should be the foundational law of the land, not the Constitution.

The belief that only Christians (and only certain "kinds" of Christians) belong in America has led to violence against non-Christian houses of worship, such as the Sikh Temple in Wisconsin, a Jewish temple in Pennsylvania, and Muslim mosques in Minnesota and elsewhere. Several people have been killed or injured in these incidents.

Christian Nationalism first emerged in the early 20th century but gained momentum in the late 1970s when conservative evangelicals rallied against progressive politics. Now, it's part of a larger cultural and political divide in America, one that breeds hostility towards those who don't fit their narrow definition of who should be a "true American."

Christian Nationalism is a fundamental challenge to liberal democracy and to the secular, pluralistic values that define it. It blurs the line between patriotism and religious fervor, equating the love of country with Christianity.

Christian Nationalism also puts pressure on churches to adopt certain far-right political stances and seeks to dilute the influence of other, non-Christian religious traditions.

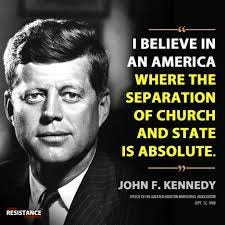

Christian Nationalism is the opposite of the fundamental American stance of separation of church and state.

Please make sure to view and act on the important information at the end of this article to help support “We Are Speaking.” Thank you!

The concept of the separation of church and state originated from the experiences of the early colonists who sought refuge from religious persecution. The principle has evolved over time, and in recent years, it has been both used and misused in the public sphere.

The seeds of the church-state separation were planted during the early colonial period in America. The colonists, many of whom were fleeing religious persecution in Europe, aimed to establish communities where they could practice their faith freely.

The idea of separating religious institutions from the government's control emerged as a means of ensuring that no single religious denomination could dominate the others, thus providing an environment of religious freedom and tolerance.

Contrary to what Christian Nationalists often state, America is not a "Christian nation." As a matter of fact, neither God nor Jesus Christ is mentioned anywhere in the United States Constitution, which is the law of the land.

In 1785, Thomas Jefferson penned the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which articulated the principle of the separation of church and state. The statute proclaimed that "no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever," thus establishing the idea that government should not interfere in matters of religion.

This statute would go on to inspire the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, ratified in 1791, which states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." The First Amendment thus enshrines the principle of the separation of church and state in American law.

According to the First Amendment, people are free to practice their religion as they please. However, people cannot impose or force their religious beliefs on others, especially in public or government environments, or attempt to eradicate or otherwise diminish other religions.

People also cannot discriminate against those who practice other religions besides Christianity or those who choose to not practice any religion at all.

Throughout American history, various Supreme Court decisions have redefined the concept of the separation of church and state. In the landmark case Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment's Establishment Clause applied to state governments as well. This decision reinforced the notion that the government should not favor one religion over another or promote religion in general.

In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), the Supreme Court established the Lemon Test to determine whether a government action violates the Establishment Clause. According to the test, a government action must have a secular purpose, not advance or inhibit religion, and not excessively entangle the government with religion.

One instance where the separation of church and state has been used effectively is in the context of public schools. Court decisions such as Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) have maintained that public schools cannot sponsor or promote religious activities or texts, preserving a neutral environment for students of diverse religious backgrounds.

Recently, Texas ruled that placing plaques or statues of the Ten Commandments at the entrances of public schools and allowing Christian Bible study during school hours is acceptable. Actions such as these are completely against the First Amendment.

There have been other instances where the concept of the separation of church and state has been misused to justify discrimination. For example, some business owners have cited their religious beliefs as a reason to refuse service to LGBTQ+ individuals, arguing that anti-discrimination laws violate their religious freedom.

While the Supreme Court's decision in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018) did not provide a definitive answer to this issue, it signaled that the Court may be more inclined to prioritize Christian "religious freedom" over anti-discrimination protections in future cases.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has made several rulings that may weaken the principle of the separation of church and state. For instance, in Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that religious institutions cannot be excluded from generally available public benefits solely because of their religious status.

Additionally, in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020), the Court held that states cannot deny public funding to religious schools if they offer such funding to non-religious private schools. Critics argue that these decisions may blur the line between church and state, potentially undermining the religious freedom that the principle was intended to protect.

The recent erosion of church-state separation protections may threaten the very religious freedom the principle was designed to protect. As such, it is crucial for Americans to remain vigilant in preserving the separation of church and state to maintain the foundations of religious freedom and tolerance upon which the nation was built.

How do you feel about the separation of church and state and Christian Nationalism? Let us know in the Substack Notes feature.

You can always leave any questions in the comments or email us.

This article is free to access for 7 days after publication. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber for $5/month or less to access all of the articles and other benefits.

This is your chance to support everything Keith and Pam do. We appreciate you!

Purchase and download your copy of the “Branding And Marketing For The Rest Of Us” eBook for Independent Authors and Creative and Solo Professionals and other valuable eBooks.

Enroll in one of the 6-course bundles designed especially for you: “Author and Book Marketing” and/or “Essential Creative Marketing.”

Purchase your copies of “Detroit Stories Quarterly” issues.

What else do Keith and Pam do?

Where else can you find us?

Click the link below to learn everything you need to know and review everything we offer for independent writers and creative and solo professionals.