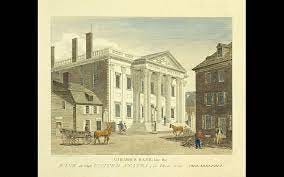

First Bank of the United States (Photo Credit: FederalReserveHistory.org)

Issue #52 American History

May 11, 2022

At the time this issue is being written, we in the United States are experiencing high inflation, rising interest rates, and a possible upcoming recession. As we deal with these issues, at least we can be assured that our banking system is relatively safe and that what money we have in the banks is relatively secure and easily accessible. It wasn’t always that way, however.

Our present Constitution was ratified in 1787, and just a few years before that, while we were still functioning under the Articles of Confederation, Alexander Hamilton and others helped persuade Congress to charter the first bank, the Bank of North America. It was located in Philadelphia, which at the time was the de facto capital of the country.

In 1784, a group of merchants in Boston founded the Massachusetts Bank, and Alexander Hamilton founded the Bank of New York. By the time General George Washington became president of the new United States in 1789, there were only three banks in the United States, and President Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton to be the first Secretary of the Treasury. Among many other banking innovations, Hamilton also founded the first national bank, the Bank of the United States, which had the power to open bank branches in various cities. Active securities markets also opened in the late 18th century, with stock market exchanges opening in Philadelphia and New York.

Banking in the 19th Century

President Andrew has been widely and falsely credited with overhauling the federal banking system. If fact, it was just the opposite.

After the War of 1812, the United States again found itself in deep debt due to the British actions against trade during the war. Congress narrowly approved the establishment of a Second Bank of the United States, but President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill and there were not enough votes in Congress to override the veto.

Why was Jackson so opposed to the Bank? Jackson lost a lot of money on a land deal for which he was paid in paper banknotes that became worthless. Therefore, in Jackson’s opinion, only specie — silver or gold coins — qualified as an acceptable medium for transactions. Since banks issued paper notes, Jackson found banking practices suspicious. Jackson also distrusted credit — another function of banks — believing people should not borrow money to pay for what they wanted.

Jackson’s distrust of the Bank was also political, based on a belief that a federal institution such as the Bank trampled on states’ rights. In addition, he felt that the Bank put too much power in the hands of too few private citizens -- power that could be used to the detriment of the government.

Jackson did not support a national bank, and instead oversaw the growth of localized state banks that primarily issued currency in coins—specifically gold and silver coins.

The Rise of the “Dual Banking System”

By 1861, just before the start of the Civil War, there were about 1600 banks founded by corporations and various states. However, while the Federal government issued money only in coins, each of those banks circulated their own paper money (banknotes), in different denominations and different colors. It was difficult and inefficient to return notes to banks between and among state-chartered banks for conversion into coins, and counterfeit banknotes were prevalent.

During the Civil War, and to help finance the efforts of the Union to fight the Confederacy, President Abraham Lincoln introduced the concept of having the federal government to charter banks, issue a uniform currency, and back the currency with U.S. bonds.

That solution worked for a while, until state-chartered banks reemerged near the end of the 19th century, giving the United States a dual-banking system, which is still in effect today. Chartering banks was often a political decision, with charters given to organizations approved by the people and party in charge at the time.

20th Century Changes in the Financial System

Until 1913 there was still no central banking system and there were several banking panics, even though the U.S. economy was the largest in the world by the early 20th century.

Finally, in 1913, Congress established a central bank, the Federal Reserve System (known as “the Fed”). In 1914, the Fed established twelve regional Reserve Banks, a system of a decentralized banking system. The Fed also set up a national check-clearing system and introduced a uniform currency using Federal Reserve Notes. The new “Fed” also had the power to expand and contract currency and credit and reduce seasonal fluctuations in interest rates. This enhanced economic stability, although these reforms did not necessarily eliminate banking crises.

After the stock market crash of 1929 and during the Great Depression that followed, President Franklin Roosevelt sponsored a number of banking reforms as part of his “New Deal.” President Roosevelt close all of the nation’s banks in March 1933. This was called the “Bank Holiday,” and by June 1933, the Banking Act or the Glass-Steagall Act, introduced federal deposit insurance (the FDIC), national regulation of interest rates on deposits, and the separation of commercial banking from investment banking. These reforms created the “Fed” as we know it today, and ushered in a long period of banking stability that lasted until the 1980s.

From the 1980s through the early 2000s, various banking deregulation initiatives were passed and banks were more easily able to make more loans, merge with other banks, and purchase new forms of securities from Wall Street and international money markets.

The Ramifications of Deregulation

The bank deregulations eventually led to cheap and easy credit, especially for mortgages, which in turn led to the devaluation of assets such as mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities. In 2007 and 2008, market funding for banks dried up, and the Great Recession, the 2nd-largest economic crisis after the Great Depression led to serious financial problems for individuals, organizations, and companies.

Unlike the 1920s and 1930s, there was not a “run” on the banks during the Great Recession because of the FDIC put in place by Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Congress. It was only because of massive interventions by the Democratic President Barack Obama and the Democratic Congress at the time that prevented the same banking and financial crises of the early 1930s. Highly criticized initiatives such as the bank bailouts and the huge loan packages to General Motors and Chrysler kept the economy from collapsing altogether. The banks have never been held responsible for repaying their bailout funds while the loan packages to the auto companies (the auto industry was not “bailed out”) were repaid early and with interest.

The 2007-2009 Great Recession

In June 2009, Democratic President Barack Obama introduced a proposal for a sweeping overhaul of the financial regulatory system of the United States, which eventually passed as the Dood-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in July 2010. The acts were passed by all Democratic members of Congress, and three Republican senators also supported the act to overcome the Senate filibuster.

Dodd-Frank reorganized the regulatory system and the Consumer Protection Agency was established by Elizabeth Warren, who was a professor at Harvard University at the time. She was appointed by President Obama.

Most Republicans and most banking executives oppose stronger regulations, even knowing that relaxed regulations lead to economic crises.

Today, even though the banking system is fairly secure, the systems themselves and banking customers also depend on digital transactions, which could be negatively affected by any local, national, or international disruption of the internet.

U.S. Banking and Economics Are Complicated

Since the late 19th century, almost all recessions and depressions began during Republican administrations that decried regulations and were ended by the subsequent Democratic administrations that for the most part attempted to help regular citizens not be under the rule of free-wheeling deregulations and tax-cutting policies and “supply-side” economics.

The GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and job growth have expanded more during the almost 18 months of the Biden administration than virtually any time in history, and the deficit and unemployment numbers are lower than they have been in decades. However, inflation is at its highest level in 40 years, and gas prices are as high as they were during the George W. Bush administration in 2008 during the Great Recession.

Job growth leads to higher wages, which in turn leads to more inflation. Raising interest rates too fast in order to cool inflation could lead to a mild recession.

It’s complicated.

We’ll see how the economy will affect the 2022 midterm elections.