The History of Standardized Testing in America

People have varied learning styles, but visual learners do best on tests.

Issue #131 Education September 7, 2022

No ads or annoying popups ever! So instead, please see the important information at the bottom of this post. Please keep those “Likes” and comments coming! Thanks!

Standardized testing in America actually started in the latter half of the 19th century. Around 1840, free public elementary education became widespread, and free public secondary education followed soon after, although the availability of high schools outside of major urban areas and to non-white students was highly restricted. Black students in the rural South often had to move to a major northern city and live with relatives or others in order to attend high school.

The United States was still primarily an agrarian society during that time, but as the Industrial Revolution expanded, most jobs in cities were service and factory jobs. Most people rarely needed an education past the 6th or 8th grades. The majority of people did not have a high school education, and even fewer obtained college degrees until after World War II when college costs were subsidized by the United States government until 1980.

My background and outlook as a student and as an educator

Only one of my four grandparents graduated from college, but the majority of their children—my parents and my aunts and uncles—did graduate from college with one or more degrees. The majority of their grandchildren, including me, my three siblings, and my twenty-three 1st cousins, also graduated from college with one or more degrees. Like many Black families in the 20th century, we were taught to get a good education and a good job. Those goals were non-negotiable.

I learned to read at about age three. I always excelled in the language arts and humanities areas. Of course, I was a “visual learner,” and reading and writing always came easily to me. I was never as good at math and science, which my parents, who were both scientists, could never understand.

Starting at about age 9, when we took family road trips, I was allowed to sit in the front seat to be the navigator as my father drove, because I was so good at reading those big paper foldable maps. My mother, who always got us lost, was relegated to the back seat.

This is one of the reasons why I excelled on the reading, writing, maps, and geography portions of the 4th grade California Achievement Test.

Most people learn in one of three ways: 1) visually (about 65 percent of learners), using seeing and reading as the primary way of accessing information, 2) auditorially (about 30 percent of learners) using hearing and speaking as their primary way of accessing information, and 3) kinetically (about 5 percent of learners) using touch and movement as their primary way of accessing information. Many people who suffer from ADHD (Attention Deficient Hyperactivity Disorder) are kinetic learners.

Babies are primarily kinetic learners (which is why they put everything in their mouths), but by about 3rd grade, most children have outgrown the need to be kinetic in their learning style. But preschoolers and 1st and 2nd graders still need to use a lot of manipulation and touching, physical movement, and group play as their primary mode of learning.

A quick check: When someone asks you how to spell a word, do you write it out to see how it “looks,” or do you spell the word out loud to yourself to hear how it “sounds?” If you do the former, you are probably a visual learner. If you do the latter, you are probably an auditory learner.

Of course, the problem is that so many words in the English language are not spelled the way they sound, and many of the words we use every day come from other languages. Not to mention that English language words are spelled differently depending on where you live in the world.

The other huge problem is that most of the curricula in schools, even starting in kindergarten, is targeted toward visual learners. The unique learning styles of auditory and kinetic learners are virtually ignored, and those are the students who end up doing poorly in school and are labeled “trouble-makers” just because they learn differently than others. They need to talk constantly and move around a lot.

My mother became a teacher after she was a nurse, and she often told me stories about her experiences with her students of different levels and those with different learning styles. When I became a teacher, I remembered what she told me.

My Bachelor's degree is actually in special education, so as a teacher I was already cognizant of the different learning styles of my students.

Unfortunately, I often got into a lot of trouble when I used different and additional teaching methods in my classrooms because I wasn’t following the current paradigm of only “teaching to the test,” meaning teaching students just enough to pass the written standardized tests.

When I allowed my students to sit and learn in groups, to learn by talking and listening to me and among themselves, or to demonstrate their grasp of the lessons by singing, dancing, performing, public speaking, or using the visual arts, I was told that my students weren’t learning or “working” because they weren’t sitting in rows filling in little circles on paper all day long.

A timeline of standardized testing in the U.S.

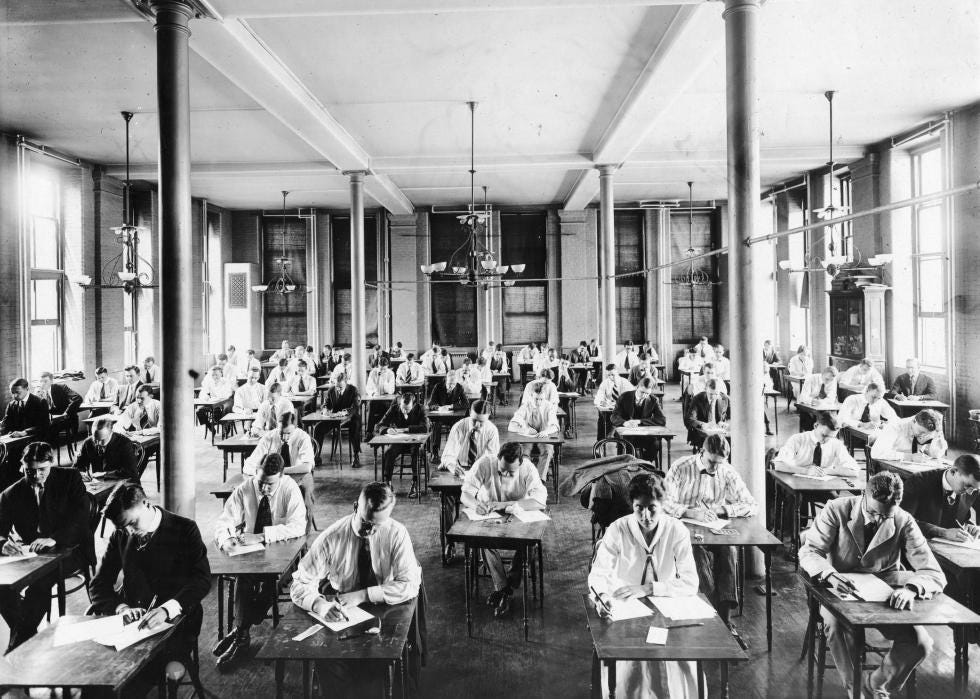

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, written standardized tests, aptitude tests, and intelligence tests came into widespread use in public schools and as university admissions tests. Most of these tests, which replaced oral exams, were developed in the United States and Europe by scientists and psychologists. By 1922, many educators, including progressive educator John Dewey, became critical of standardized testing for failing to take into account different learning styles and for not realizing how students could also learn through their lived experiences.

In 1925, intelligence and achievement tests were used widely to classify students in almost all public elementary and high schools. Students were grouped into predetermined educational paths such as “college prep” and “vocational training.”

In 1926, the 90-minute Scholastic Aptitude Tests (SATs) were introduced with over 300 questions on vocabulary and math. In 1936, the Iowa Assessments tests were widely adopted around the country. In 1959, the American College Testing (ACT) exams with four sections: math, English, social studies, and natural science. The time limit for each section was 45 minutes.

In 1965, as part of the “War on Poverty,” President Lyndon Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). The program used standardized testing to assess student progress and teacher accountability.

In 2001, President George W. Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). This law was aimed at holding schools accountable for students’ achievements, no matter the students’ differing cultures, backgrounds, socioeconomic statuses, or learning styles. Under the law, states had to test students regularly on reading and math, report the results, and ensure that students reached levels of proficiency. Failure to comply or achieve the goals put schools at risk of losing federal education funds. This is when “teaching to the test” became mainstream in public schools, and the constant testing and test preparation replaced studying the arts, music, and creative subjects. Even physical education was pushed to the background to make time for more testing.

Recently there has been a growing backlash against standardized testing, even for universities and professional graduate schools like law and medical schools. A 2015 study revealed that the average American public school student was forced to take about 112 mandatory standardized tests from preschool through 12th grade. Yet American students still lag behind other countries in educational achievement.

During the pandemic, many school systems realized that inequitable standardized tests took up a lot of time and energy and were much less effective for assessing what students learned than previously thought.

Also during the pandemic, many more parents and educators not only realized that students learned differently, but also that children had many different lives and learning experiences that affected how they learned and how their learning should be evaluated.

Hopefully, the experiences of students during the pandemic, as well as the growing disillusionment with the testing industry among educators, parents, and students will lead to the end of the country’s obsession with high-stakes standardized tests.

How did you do with standardized testing? Are you a visual or auditory learner? Let us know in the comments!

Help us to grow!

“We Are Speaking” is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and podcast episodes and to support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. We publish 7 days/week and 28+ issues/month. You. can upgrade your free subscription to the paid level. It costs monthly and annual paid subscribers less than 35¢ an issue. Thank you!

Thank you for checking out some of the books and businesses of the TeamOwens313 Global Creative Community:

Detroit Stories Quarterly (DSQ) Afro-futurism Magazine

The Mayonnaise Murders: a fantasy mystery novel by Keith A. Owens

The Global Creative Community Brand and Marketing Academy: Training and Group Coaching for Independent Writers and Creative and Solo Professionals

Pam’s Branding and Marketing Articles for Independent Writers and Creative and Solo Professionals on LinkedIn

“We Are Speaking” is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and podcast episodes and to support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.