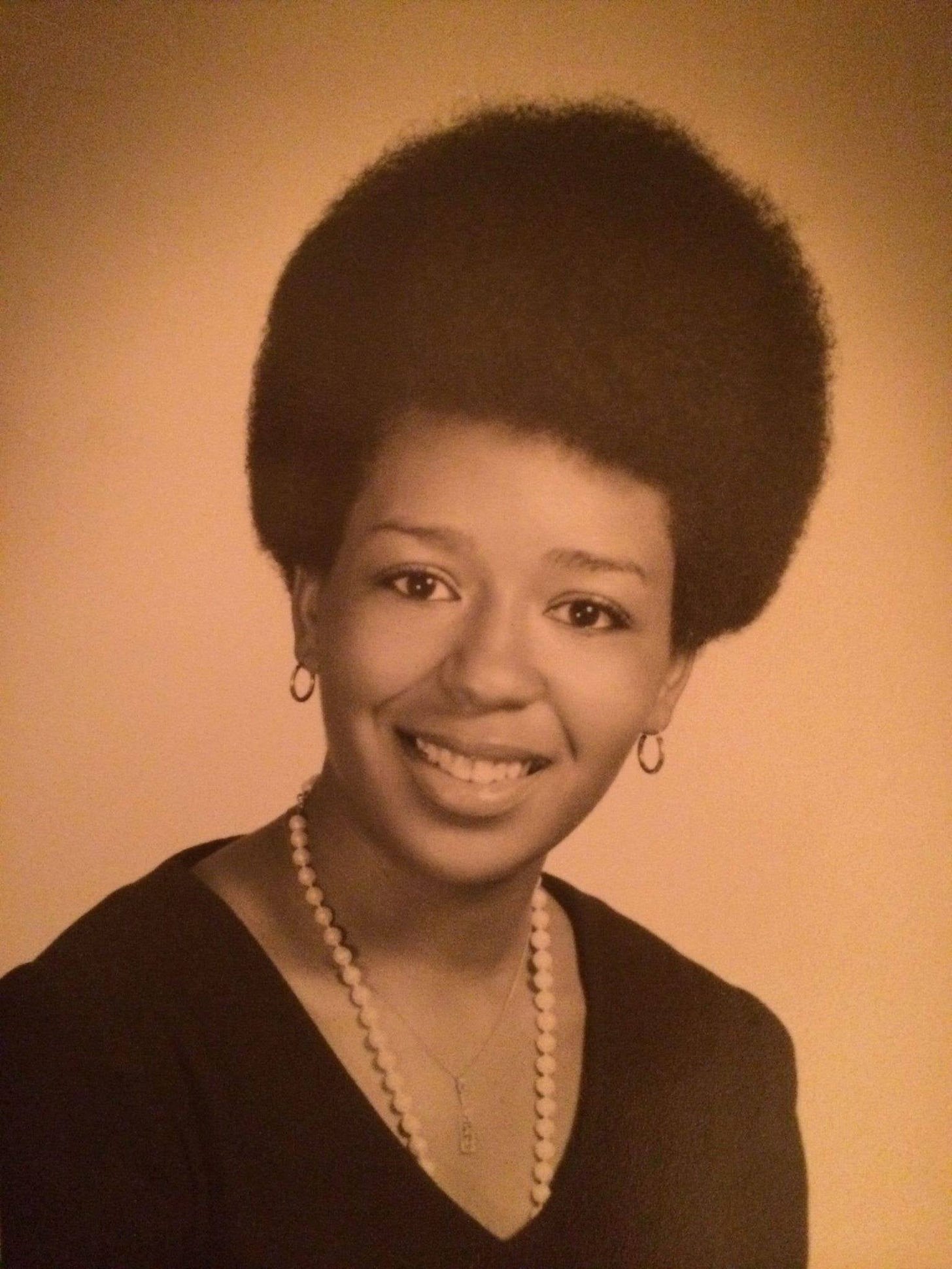

My graduation photo from 1971 for my Bachelor's degree.

By Pamela Hilliard Owens

(Please scroll to the end of this article to comment, share, subscribe, and get the app. Thank you!)

Even as far back as the 18th century, white people have had trouble with the natural state and hairstyles of women of African descent. It never mattered that our texture is what we were born with, and Eurocentric standards of beauty were never meant for us.

In New Orleans in the late 18th-century, there was an increase in the populations of free Africans, Creoles, and “mulattos,” much to the chagrin of the leaders there. The women dressed their bodies and their hair in such an elaborate manner that they were becoming attractive to white men, and were also looking more wealthy than they were, which was also a threat to white women.

So in 1786, Spanish colonial Governor Don Esteban Miró enacted the Edict of Good Government, also referred to as the Tignon Laws, which “prohibited Creole women of color from displaying ‘excessive attention to dress’ in the streets of New Orleans.” The law forced them to wear a tignon (scarf or handkerchief) over their hair to show that they belonged to the slave class, whether they were enslaved or not.

All through the 19th century, many slaves and former slaves also felt they had to cover their natural hair because it was “different” from the hair of white women.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the use of the straightening comb became popular, and it wasn’t until the civil rights and Black power movements of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s that Black women started proudly wearing their hair in Afros and cornrows.

However, in the corporate world and in many parts of society as a whole, wearing natural hairstyles was still problematic for Black people. Black women, especially if they were in the public eye, were discouraged to wear their natural hair and were told it was “unprofessional.”

Black children in school were told that natural hairstyles, especially braids and locs, did not meet the “standards” of the school. Girls were discouraged from wearing long dreadlocks, and boys were told that they had to cut their Afros or locs.

A couple of years ago, a young man who was the valedictorian of his senior class was told he could not participate in the graduation ceremonies unless he cut off his locs.

The white coach of another Black young man literally cut the boy’s locs with scissors himself just before a sports event.

Although in the past few years, Black women wearing natural hairstyles has become more acceptable, there is still a great deal of discrimination against adults and children who style their hair in ways that showcase the way it naturally grows out of their heads.

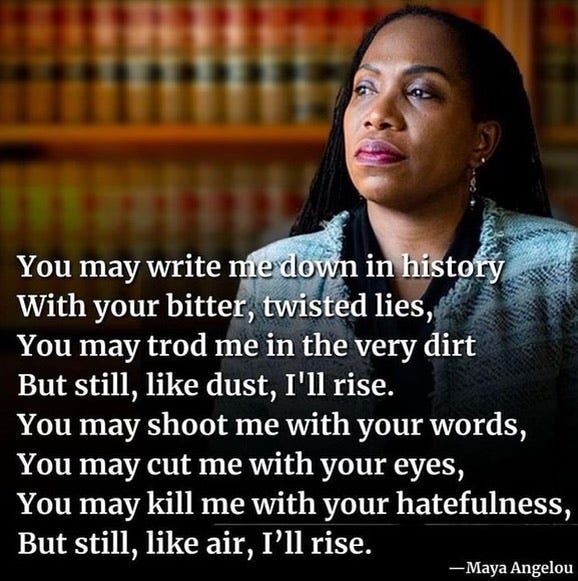

The fact that the first Black woman nominee for the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) has always recent years worn a protective natural hairstyle called “Sister Locs” has not stopped the perception that Black hairstyles are for the most part still considered “unprofessional” in work and school settings.

This discrimination has become so problematic that the Democratic-led US House of Representatives finally recently passed the CROWN Act that bans race-based hair discrimination in the workplace.

The CROWN Act, an acronym for “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair,” seeks to protect Americans against bias based on hair texture and protective styles.

The bill, introduced by Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, states that “routinely, people of African descent are deprived of educational and employment opportunities” for wearing their hair in natural or protective hairstyles like locs, cornrows, twists, braids, Bantu knots, or Afros.

The bill will now go to the Senate to be passed, although many Republicans complain that the bill is not necessary because there are already laws on the books that deal with workplace discrimination.

It seems almost ridiculous that a Federal law has to be put in place to protect a naturally-occurring condition from leading to personal and professional discrimination, but this is where we are.

At least we’ve come full circle from the laws passed in the late 18th century against natural hairstyles to laws passed to protect natural hairstyles. I guess that’s progress…