Who They Were and Why Their Work Mattered

From the latter part of the 19th century, throughout the 20th century, and well into the 21st century, tens of thousands of known and unknown people of all races worked tirelessly for the civil rights of their fellow American citizens as supposedly guaranteed by the United States Constitution ratified in 1789 as well as the twenty-seven amendments added throughout the two hundred and thirty-one years since.

However, starting with the mid-20th century, the era of the modern Civil Rights Movement reached its zenith, and the leaders of seven separate but related civil rights organizations did the majority of their work.

Most historical organizations and major media discuss the “Big Six” Civil Rights leaders and organizations, but they conveniently ignored one of the best-known women of that time, Dr. Dorothy I. Height, so I am discussing here the “Big Seven.” Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is the most well-known, and there are many other contributors who could be named, but for this Medium story, and just following the death of the last of the Big Seven, Congressman John Robert Lewis, I will concentrate on these special leaders, almost all of whom attended the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Justice.

Black Lives DO Matter

That’s Why MY Life Mattersmedium.com

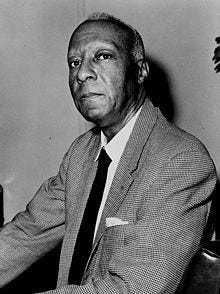

1. Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 — May 16, 1979): The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

A. Philip Randolph was a socialist politician and labor leader who, in 1925, organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first labor union for employees of the Pullman Company, which hired many African-Americans to work on the national train routes. During the Second World War, Randolph initiated the “March on Washington” movement, which was the forerunner to the 1963 March that he initiated. During the 1940s, Randolph pressured Presidents Roosevelt and Truman to issue executive orders that resulted in the full integration of the industries that worked on the war effort as well as the armed forces. During the 1963 March on Washington, Mr. Randolph ensured that the labor movement was adequately represented.

2. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 — April 4, 1968): The Southern Christian Leadership Conference — SCLC

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was the most famous of the civil rights leaders. He began his civil rights work with helping to lead the 1955 Selma Bus Boycott that ultimately led to the integration of public transportation facilities nationwide. Dr. King was a Baptist minister and a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, one of the leading Black Greek fraternities. He entered Morehouse College at age 15, and received his doctorate degree in 1955 at age 26. Dr. King, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously in 1977 after his assassination in 1968, was widely reviled by many, even after his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington. It was not until years after his death, and after a national holiday was established in his honor, did most people finally honor him and his nonviolent work for civil rights for all.

3. Whitney Young (July 31, 1921 — March 11, 1971): The National Urban League

Based on his own experiences with employment discrimination in the South and discrimination during his military time during World War II, Whitney Young transformed the National Urban League from a small, passive civil rights organization into one that fought extensively for jobs and justice. Under his leadership, after he was elected as executive director of the organization in 1961, he introduced many new educational policies and programs that particularly assisted Black Americans who were new to the country’s cities to find and keep employment in the public and private sectors.

4. Roy Wilkins (August 30, 1901 — September 8, 1981): The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — NAACP

Roy Wilkins, who served as executive secretary and then executive director of the NAACP from 1955 through 1977, believed that overall civil rights could best be achieved through legislative means. However, he also worked hard to support civil rights activists in Mississippi when their bank accounts and credit lines were negatively affected by members of the White Citizens Councils. During his tenure as editor-in-chief of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, Wilkins was responsible for working with J. Edgar Hoover to spread negative press about the entertainer and activist Paul Robeson and the accusations that Robeson was a communist and a threat to the United States. Mr. Wilkins helped to organize and participated in the 1963 March of Washington and the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965. He worked closely with Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter and was opposed to the more militant “Black Power” movement. Mr. Wilkins was a member of Omega Psi Phi, a leading Black Greek fraternity, and he was awarded the NAACP Springarn Medal in 1964.

5. James Farmer (January 12, 1920 — July 9, 1999): The Congress of Racial Equality — CORE

The Congress of Racial Equality, a pacifist organization that was dedicated to nonviolent protest, was co-founded in 1942 by James Farmer who became its executive director in 1953. CORE was responsible for organizing the majority of sit-ins and freedom rides that battled segregation in restaurants and on transportation. While arranging protests in 1963, Farmer was jailed for “disturbing the peace” and was unable to attend the 1963 March on Washington. Farmer resigned from CORE after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, becoming an educator at the HBCU Lincoln University near Philadelphia. He was later hired by President Richard Nixon to be the Assistant Secretary for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, but resigned the next year. Mr. Farmer identified as a member of the Democratic Socialist Party and finally retired from teaching in 1998, shortly before he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton.

6. Dr. Dorothy Irene Height (March 24, 1912 — April 20, 2010): National Council of Negro Women

Dr. Dorothy I. Height was a civil rights and women’s rights activist who was the first civil rights leader to recognize the inequalities for women and for African-Americans should be intertwined. Known for her beautiful hats that matched every outfit, Dr. Height served as the president of the National Council for Negro Women for over forty years. In her youth, she became quite active in integrating the local YWCA in Pittsburgh as well as anti-lynching activities. Dr. Height was an award-winning orator. She was accepted to Barnard College in 1929 but was denied admittance because the college policy was to admit only two Black students per year. Dr. Height instead received two degrees from New York University and a postgraduate degree from the Columbia School of Social Work. She worked with and consulted for all of the U.S. presidents from Franklin Roosevelt through Barack Obama. Dr. Height was also a member of Delta Sigma Theta, one of the leading Black Greek sororities, and served as its president from 1947 through 1956. Dr. Height worked for women’s rights all through her career and was an organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. However, even though she was a confidant of Dr. King, because she was a woman, she was not allowed to speak at the March. She went on to found or be actively involved with many women’s rights organizations. She also spoke against unethical research activities, spurred by the Belmont Report about the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Dr. Height was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton and was an honored guest at the first inauguration of President Barack Obama, who gave the eulogy at her funeral in 2010. Dr. Height is the only African-American woman to have a federal building in Washington D.C. named after her. James Farmer fought for her inclusion as one of the “Big Six” civil rights leaders, but her name was removed from the unofficial honor because she was a woman.

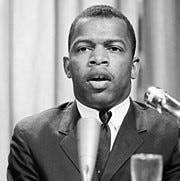

7. Congressman John Lewis (February 21, 1940 — July 17, 2020): The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The leadership of John Lewis in the civil rights movement began with his appointment as president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and as one of the original thirteen Freedom Riders. At age 23, he was the youngest speaker at the 1963 March on Washington. He participated in many sit-ins and other freedom marches in the 1960s, famously almost losing his life during the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march after having his skull split open by Alabama state troopers. Named “Bloody Sunday,” the events that day led directly to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. After his death, members of the Alabama and Georgia State troopers accompanied his casket across the Edmund Pettis Bridge one more time and carried his casket to the hearse from the funeral held at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta once pastored by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. President Barack Obama gave the eulogy at the funeral where Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton also spoke. John Lewis represented the 5th District of Georgia, which includes Atlanta, from 1987 until his death in 2020. Mr. Lewis was awarded the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2001, and President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010. It is recommended that the Edmund Pettis Bridge and the 2020 Voting Rights Act be re-named after Congressman John Lewis.

These renowned seven civil rights leaders are listed here in order of their deaths, but as we read and learn more about their lives and work, we need to ask ourselves, why was their work needed at all? Why are we still fighting for equal rights for all Americans almost one quarter into this century?

About Me

I am a native Detroiter, a wife, mother, grandmother, solopreneur, and homeowner. I would love for you to follow me on my personal Facebook and on my personal Instagram. Any opinions expressed in this publication are my own.

I invite you to read the stories in my other publications: Your Business Your Brand Creatively and Detroit Ink Publishing.